Novel approach to antibiotic discovery earns SU biochemist place in US$60 million global consortium

- The Gram-negative bacterium Klebsiella pneumoniae is one of the leading causes of antimicrobial-resistance deaths worldwide.

- New strategies are urgently needed to fight these multi-drug resistance bacteria.

- Grant signifies a significant investment in Stellenbosch University’s ability to develop novel therapeutic drugs.

Prof Erick Strauss from Stellenbosch University’s Department of Biochemistry is leading one of two African project teams selected to participate in a global consortium to transform antibiotic discovery to counter the growing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis.

View video interview here.

In a media release the Gates Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and Wellcome announced $60 million in grant funding over the next three years to support 18 projects led by research teams across 17 countries, all exploring novel approaches to antibiotic discovery. The research teams were selected for their potential to transform antibiotic discovery for Gram-negative bacteria, especially Klebsiella pneumoniae - one of the leading drivers of AMR-related deaths worldwide.

The Gram-Negative Antibiotic Discovery Innovator (Gr-ADI) will function as a first-of-its-kind consortium where multiple funders and research teams openly share data and learnings and work collectively to accelerate the discovery of urgently needed antibiotics. It is the first investment of the $300 million global health research and development partnership launched by these three philanthropic organizations in 2024.

The two project teams from Africa are led by Strauss, a chemical biologist, head of the Department of Biochemistry and co-director of the Africa Centre for Therapeutic Innovation (ACTI) at SU, and Prof Stephen Dela Ahator of the University of Ghana.

Strauss’s team consists of co-investigators Prof Andrew Whitelaw from the Department of Medical Microbiology in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Prof Adrienne Edkins of Rhodes University, and the Ersilia Open-Source Initiative in Spain, led by Dr Miquel Duran-Frigola. Prof Willem van Otterlo from the Department of Chemistry and Polymer Science at SU will be assisting the team in achieving its chemical synthesis goals.

New strategies urgently needed

Strauss explains: “Traditional antibiotics and other antimicrobial drugs work by inhibiting or interfering with processes that are essential to the growth and survival of the disease-causing organism, such as the making of proteins or the generation of a new cell wall. If the concentration of the antibiotic is maintained at effective levels (by adhering to the prescribed dosage), the pathogen will be killed or at least prevented from multiplying, giving the immune system time to fight the infection.”

But Gram‑negative bacteria are increasingly showing resistance to the currently available antibiotic drug classes, complicating treatment of infections. New strategies are urgently needed to fight these bacteria, specifically ones that work differently from those currently in use, as this will reduce the chance of resistance to the new treatment.

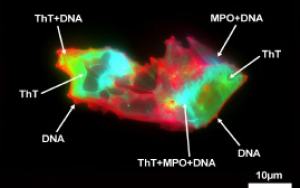

The new approach that Strauss’s team will explore is inspired by successes in the cancer research field: Instead of inhibiting deleterious proteins, a cell’s native protein degradation machine can be hijacked and deployed to destroy the target protein. This process, called targeted protein degradation, makes use of PROTACs - specially designed bifunctional molecules – to achieve this.

While PROTACs have been studied as cancer therapies for more than 20 years, bacterial PROTACs, or BacPROTACs – molecules that cause pathogenic bacteria to destroy their own essential proteins – were only first described as potential treatments of Mycobacterial infections (including tuberculosis) in 2022.

In 2023 a team led by Strauss received funding from the Gates Foundation and LifeArc as part of their investment in the Grand Challenges African Drug Discovery Accelerator (GC ADDA) to apply this new strategy to develop a drug to target multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis.

“What is especially exciting about this approach is that the drug is recycled, since it effectively acts as a fishing rod with a baited hook to catch the target protein; just as one needs only one fishing pole to catch many fish, the drug can be used repeatedly to exert their destructive effect on the target protein in question. This suggests that lower doses may be needed, and that the effects may be longer lasting,” he adds.

Strauss’s team will now channel the knowledge and expertise they gained in the tuberculosis project into establishing a BacPROTAC development workflow focused on Gram-negative bacteria, starting with Klebsiella pneumoniae. The eventual goal would be to use such a workflow to identify BacPROTACs that promote the destruction of any validated drug target or resistance-inducing factor that can be shown to be degraded by the pathogen’s endogenous protease, and for which a target-engaging ligand (the baited hook) can be identified.

“We are excited to be joining the Gr-ADI consortium, and to be able to contribute to solutions to health challenges for which Africa carries an especially heavy burden. It is a significant investment in our ability develop new therapies for infectious diseases,” he concludes.